When it comes to improving operational efficiency, many cite the famous quote “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” This quote is often attributed to W. Edwards Deming (pictured left), the man who revolutionized the Japanese manufacturing industry, or Peter Drucker (pictured right), considered by many as the father of modern management theory.

Apparently neither of them actually said this quote or used it in the way it is generally perceived according to these sources (citation 1, citation 2, citation 3).

While some will debate the merits of the quote, stating that there are some important things that simply can’t be measured but still have to be managed, it’s hard to dispute the value of data when it comes to managing and improving operational efficiency.

How Deming Impacted Quality

According to this biography, Deming helped turn Japan into an industrial powerhouse by teaching manufacturers how to produce top quality products economically, this is often associated with Total Quality Management (TQM). In particular, Deming criticized the approach U.S. manufacturers used to manage quality control – a system where products were inspected for defects after they were made.

Deming believed it is better to design quality into the the manufacturing process so quality was built in from the start.

Quoting from the biography: This made economic sense. When a poorly made product came off the production line, a company faced two undesirable options:

- It could scrap the piece—wasting the material, labor, energy and financing costs that went into making it.

- It could ship the product and risk alienating its customers.

Deming believed that if you made quality products from the start, you’d save money and win customers. To prove this, he used statistical data to document the manufacturing process relating to improving operational efficiency, product quality and managerial success.

Ask companies like Toyota, Panasonic and Sony how that worked out for them. (I think they’d say pretty darned well.)

Improving Operational Efficiency in the Produce Industry

Yet, for most of the produce supply chain, we inspect for quality after the produce is delivered to the customer. The result is that grocers typically waste 10 to 12 percent of their fresh produce, according to the NRDC’s Wasted Report.

Can Deming’s approach be applied to the produce industry? Can data deliver value that impacts quality? Can we engineer quality or freshness into the fresh food supply chain?

YES!

What Impacts Freshness and Quality?

One of the most significant aspects of produce quality is its freshness – also known as remaining shelf-life. The freshness of produce is impacted by harvest conditions and post-harvest processing and handling.

Zest Labs research has shown that most of the impact on freshness occurs within the first 24-48 hours after produce is picked or cut. Once it is harvested, it has a “freshness capacity” which is the maximum amount of shelf-life for the produce if handled in perfect conditions. For example, strawberries have a freshness capacity of about 12 to 13 days. Romaine hearts about 18 days.

But, if the produce sits in the field for a few hours at 80 or 90 degrees, it’s going to lose shelf-life more rapidly than if it is immediately moved to the pack house and precooled. For example, for every hour a pallet of produce spends in the field, it will lose about one day of shelf-life. If it waits three hours, that’s three days.

The process from harvest is typically:

- Moving the produce from the field to the packing house as quickly as possible. This is called the field-to-yard or cut-to-yard time. Delays impact shelf-life.

- Precooling is the process of removing the field heat from the produce and reducing the temperature, typically to about 34 degrees Fahrenheit. The duration from field harvest to precooling is called the “Cut-to-Cool Time.” It’s also important to ensure that each pallet is properly precooled. Often, precoolers run to set times and assume that each pallet entering the precooler is at the same temperature. But, if one pallet enters the precooler 10 degrees warmer than another, it may not be sufficiently precooled which impacts shelf-life.

- Moving to cold storage and storage time-to-shipment. Sometimes produce is precooled and then stored in the yard before entering cold storage. This causes the pallets to reheat and this impacts shelf-life.

Process Adherence

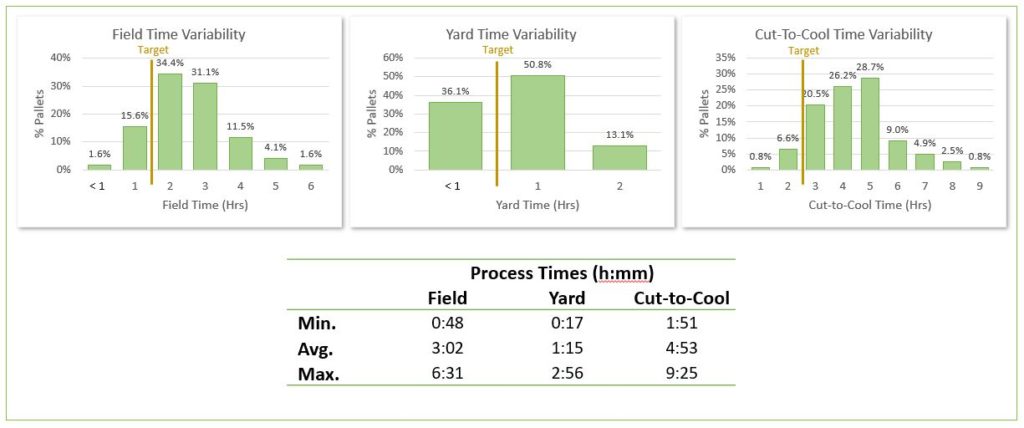

Growers and shippers have guidelines for these processes. For example, they may state that all pallets should have a field-to-yard time of less than two hours and a yard dwell time (the time between yard entry and pre-cool entry) of less than one hour. It may be assumed that these guidelines are being met, but are they?

Sometimes. But, without data, you don’t know. Without data you can’t identify where problems are occurring that can impact freshness and shelf-life.

The case study below shows that guidelines or targets are not being consistently met and there’s significant variation at each process step (field-to-yard, yard to precool dwell time and the consolidated cut-to-cool time). For example, the target cut-to-cool time was less than three hours but, in fact, the average was four hours and fifty-three minutes with some pallets waiting eight to nine hours!

The Data Makes the Difference

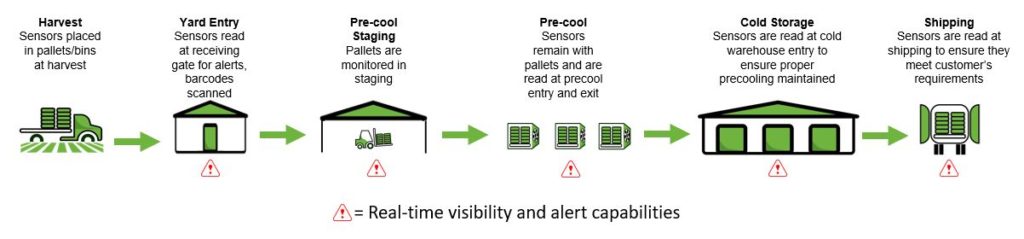

This is where having data makes the difference. Zest Fresh | Metrics provides trending and real-time information and insights to growers and suppliers to help them improve operational efficiency and process adherence. By applying IoT temperature sensors to each pallet beginning at harvest and autonomously collecting that data at each step along the way, we can improve delivered freshness and achieve multiple benefits:

- The grower/supplier can see the big picture with regards to their processes. In the case above, there were systemic issues with field-to-yard time and yard dwell time that required attention.

- The grower/supplier can receive real-time alerts when pallets are “out of compliance” and prioritize those pallets for precooling or getting them into cold storage. This minimizes the impact of process variation and helps to ensure that their produce has sufficient freshness to meet their customers’ requirements.

- Pallets can be ranked on a “good, better, best” scale, based on each pallet’s handling. “Best” pallets can be shipped to the furthest destination while “good” pallets can be sent to closer destinations to ensure that each arrives with sufficient freshness to meet the customer’s freshness requirements. This reduces waste and improves customer satisfaction.

- This approach avoids the pitfalls that Deming mentioned with regards to traditional quality assurance approaches:

- There’s no need to scrap or waste the produce, labor, energy and financing costs that went into making it.

- There’s little to no risk of shipping poor produce and alienating your customers by having it spoil in the grocer’s distribution center or on their store shelves or with their customers.

Improving Operational Efficiency Benefits the Brand

As noted in our August 20, 2019 blog on produce brand marketing, many growers and suppliers are increasingly trying to differentiate their brand among consumers. One way to differentiate is based on consistently delivering a fresher, superior product. With Zest Fresh | Metrics, growers and shippers can differentiate their produce from competitors based on delivered freshness and providing a more consistent experience for their customers.

Zest Fresh is like TQM to improve operational efficiency for the fresh food supply chain.